It has been more than 80 years since a government-ordered report into the conditions inside Canada’s prisons recommended nothing less than “radical change.”

The better part of a century later, there are concerns that the wisdom of that report has been lost. Lawyers and human rights advocates say conditions in Canada’s prisons and jails have deteriorated to the point of crisis. Administrative segregation, overcrowding, arbitrary lockdowns, a lack of access to counsel are all problems that have become shockingly common.

Deteriorating conditions are at a crisis point. It will take something radical to get the government to act. Our prison system has been described by many as one that has steadily turned away from rehabilitation, instead favouring longer and longer sentences. Our system has become tougher on Indigenous offenders and those with mental health issues as well. It’s a system that has employed solitary confinement as a matter of convenience for the prisons, or as a way to cover resource shortages for example. While correctional officers manage staff shortages for example, prisoners remain locked in their cells for longer periods than normal, including those in general population and protective custody ranges, outside typical segregation settings. In provincial jails and federal prisons, inmates – most of whom have not been convicted, are often ‘locked down’, meaning they cannot leave their cells even for a shower or a phone call, sometimes for many days at a time.

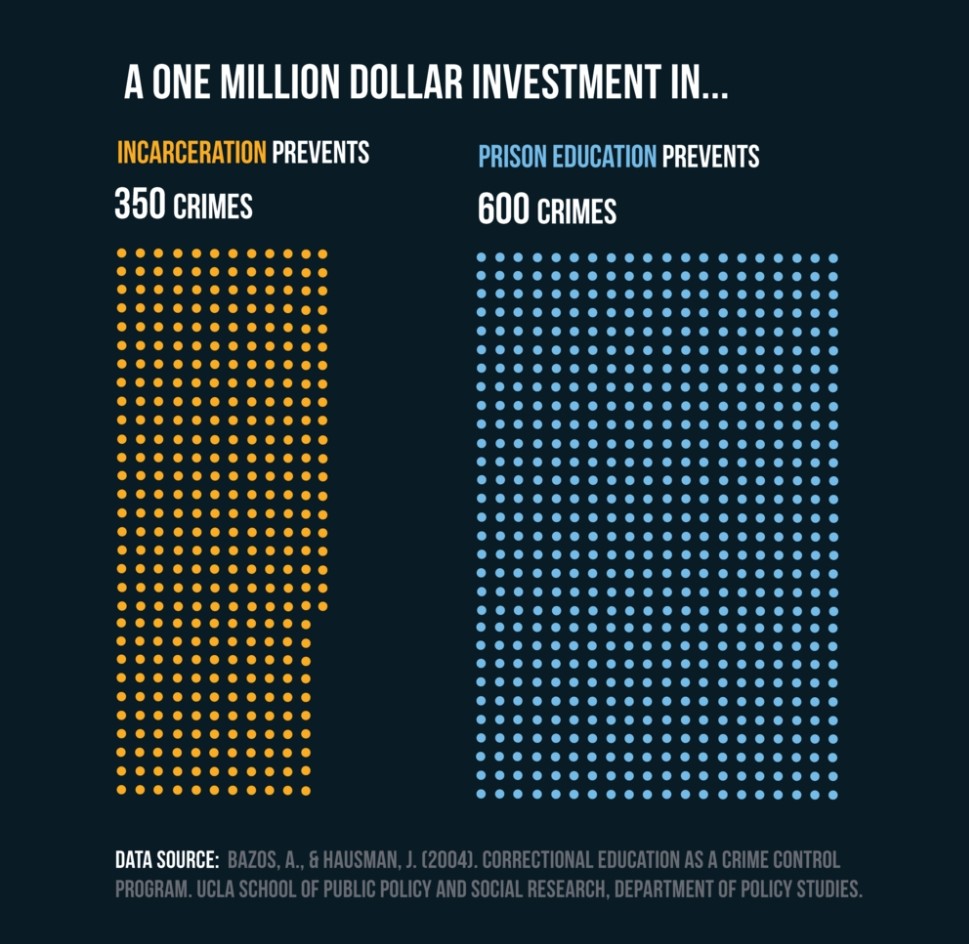

Access to education and vocational training is both cheaper and more effective at keeping people from returning to prison than say, longer sentences, punishments, increased surveillance, use of solitary confinement or electronic monitoring. In fact, as the following figure depicts, on average, prison education prevents 600 crimes while incarceration alone only prevents 350.

Although Ottawa has yet to deliver on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s recommendations, it is still widely suggested that Canada move away from mandatory minimum sentences, leverage conditional releases, and expand support services for all inmates, in and out of prison.

In my opinion, lawyers need to start weaponizing Section 24.1 of the Charter to seek sentencing remedies for their clients unfairly put in segregation, and who are refused basic healthcare, or denied support services necessary for rehabilitation. The reason is simple – until individual inmates start seeing their sentences reduced, or start being freed outright, the government will have no real incentive to act.

To view full article or to access latest copy of the Correctional Investigator Report, please visit:

http://www.intersectionalanalyst.com/intersectional-analyst/2017/7/20/everything-you-were-never-taught-about-canadas-prison-systems

https://www.oci-bec.gc.ca/cnt/rpt/index-eng.aspx